things that matter:

quotes to ponder

family things:

fun things:

|

Tale of the

Hoernersburg: Heavy Burdens Many hundreds of years ago, deep in the Middle Ages, lived a ruthless baron and his son, Rolf. Baron von Skitter was a stout man with dark black hair. He wore a patch over his left eye. Along the banks of the Rhine River in Germany, the baron built his mighty-make-believe castle, the Skittersburg. Baron von Skitter was one of several “robber barons” who had built their castles along the Rhine. From his castle, he stopped boats traveling along the wide river and forced them to pay heavy taxes if they wanted to pass. He stopped the boats by stringing a giant chain across the river. If they paid the tax, he would lower the chain deep into the water and allow the boat to pass. If they somehow tried to sneak through, he would hurl large rocks from the mangonel high on the castle tower.

From this castle, he also ruled the

villagers in the nearby town of Legoland with an iron fist. He burdened the

townspeople with taxes and unjust laws. Outside of the town, the serfs were even less fortunate than the villagers. The serfs, who where poor peasants, cared for the baron’s fields. Among other taxes, they had to pay a wood-penny to collect firewood, a bodel-silver for housing, and an agistment to graze their animals in the forest. Even when a serf died his family had to pay a tax called a heriot, which was the dead man’s best beast, or the equivalent amount in money. Unlike the villagers, who were mostly freemen and could come and go as they liked, the serfs had few rights. They were almost slaves as they could not move away from the baron’s lands. They could not marry without the permission of the baron. And if a serf had children, his children were automatically serfs as well. Only the baron could set a serf free. Although the serfs could grow a meager amount of food on small strips of land, they did not own the land. They also had to care for the baron’s land. When the baron’s land, or demesne, needed farming, the baron could demand that the serf work on them without pay. When harvest time came, the serfs first had to harvest the baron’s land before harvesting their own. The baron was a cruel tyrant. Although he was obligated to protect the townspeople and serfs, he rarely did so. His laws and punishments were harsh. Freemen in the town had the advantage of a trial by their neighbors, but serfs were usually tried by the baron himself – and the baron was rarely fair. To determine if a serf was guilty, the baron often held a “trial by ordeal”. In “trial by boiling water”, the accused person plunged his hand into a bucket of boiling water. The hand was then bandaged. After a few days the bandage was removed. If there was a blister half as big as a walnut, which there usually was, the man was considered guilty. In “trial by fire”, the accused person had to carry a red-hot piece of iron in his hands. If there were no burn marks, which was unlikely, then the person was considered innocent. In “trial by drowning”, the accused person was thrown into the river. If he drowned, he was considered innocent. If he floated, he was considered guilty and immediately hung on the gallows. Although people sometimes deserved their punishment, sometimes they did not. For minor crimes, such as lying, the prisoner was chained to a post and made to wear an iron mask with a long metal tongue sticking out. For cheating, the prisoner’s feet were locked in the wooden stocks for a day. People passing by would throw rotten fruits, vegetables, and eggs at him. Someone who had done an evil deed might have the letter “M” (for malefactor) branded permanently on his forehead. For especially bad crimes, the criminal would be hung on the gallows to slowly choke to death. If he was a higher-ranking or richer criminal, he would be fortunate to have his head cut off instead, which was a quick death. The baron cared little about the people under his authority. He mostly worried about himself. Rolf, the baron’s only son, was not much different. He was a brown-haired boy of eleven years old. At the age of seven, he had become a page. In a couple more years, he would become a squire, and then finally dubbed a knight. Honorable knights practiced a code of chivalry – bravery, courtesy, honor, and gallantry towards women. It did not appear that Rolf would be an honorable knight.

Not too far from the castle, in one of the baron’s vineyards on the steeply-sloping hills of the Rhine River valley, lived a poor serf named Friedrich. It was here on the baron’s land that Friedrich worked the vineyards during the day. During harvest time, Friedrich would load his funnel-shaped wicker basket with grapes, hoist it on his back, carry it down to the village, and dump the grapes into a large open barrel. Girls would then climb bare-footed into the barrel and stomp the juice out of the grapes. Later, the juice would be made into choice wine and shipped up and down the river to be sold for a high profit – a profit which the baron kept for himself. As Friedrich worked in the vineyard, he would listen for the bells of the Monastery Church of the Nativity. At noon the bells in the church tower rang to signal people in the entire river valley to stop whatever they were doing and pray the Angelus. When they rang, Friedrich would stop, take off his hat, bow his head, and pray:

During the evenings, Friedrich would sit on the slopes and play his horn, which he had carved himself. His music could sometimes be heard for miles up and down the river valley. His favorite tune was Ave Maria, which he played so sweetly, that it almost made you cry. Friedrich was a righteous man and tried to do everything for the glory of God. Even though his work was back-breaking at times, it helped him all the more unite his suffering with Christ’s Passion, especially the Carrying of the Cross. Friedrich’s wife, Marta, was a beautiful and loving woman. It was her job to shear the baron’s sheep. After she sheared the sheep, she took the wool down to the spinner in the village. The spinner spun the wool into yarn. The weaver made the yarn into cloth, and the tailor made the cloth into clothes. But Marta could not afford to buy clothes from the tailor. They were too expensive for poor serfs like herself and her family. Instead, Marta made all their clothes by spinning and weaving and sewing the cloth herself.

The men wore linen shirts and

breeches, which were made from the flax plant. Underneath, they wore prickly

woolen underpants. They held up their baggy underpants with a piece of

string tied around their waste. The women wore a linen smock covered with a

loose-fitting woolen tunic. Their clothes were never dyed because dye cost

too much. When it was cold, they wore a long tunic on top. They were too

poor to afford hose (long woolen stockings) to keep their legs warm. Marta tried to make meals a special and dignified time for her family. She always covered the table with a linen tablecloth. Before eating, everyone washed their hands in a metal bowl. Friedrich sat at the head of the table in the only chair. The others sat at the sides of the table on benches. Before dinner, they always thanked God for their food and asked Him to bless it. When the harvest was good, they ate mostly the same modest meal every day – bread and a thick bean and pea soup called pottage. They drank home brewed-ale poured from a pottery pitcher. When the harvest was bad, they often went hungry. Even though life was hard, Friedrich and Marta journeyed together towards God – that is, until Marta died of the bubonic plague – also called the Black Death. Marta caught the plague while helping others who were sick. Eventually, she and her young daughter Elise died of it. In fact, one of every three villagers died of the plague. Many who died helping the sick were later added to the Church’s official list of saints, like St. Aloysius Gonzaga. Marta left behind three sons for Friedrich to care for. Their oldest son, Johann, was fifteen. He liked to tinker with things and fix them. Then there was Mark, who was a bright boy of thirteen. Finally, there was Franz, who took after his father. Franz just happened to be the same age as the baron’s son, Rolf. But Franz was much different than Rolf. Franz was such a kind boy that he wouldn’t hurt a fly. He loved to listen to his father’s horn. He would sit silently and think of the Holy Virgin Mary as his father played the Ave Maria.

Fair Once or twice a year, a fair was held in the Town Square in front of the Cathedral. Traders came from far and wide to set up tents and booths, from where they would shout their wares: “Roasted chestnuts – get ‘em while they’re hot!” “Apples, big round apples!” “Knives so sharp they’ll split a hair!” “Silk cloth from the Orient.” “Pig’s ears. Get your pig’s ears!”

The potpourri of smells mixed

together was remarkable – the malty smell of freshly brewed ale; melted fat

from the candlemaker’s atelier (workshop); dead fish recently caught from

the river; the tanner’s solution of water and dog excrement for making

leather; roasted chestnuts; horse droppings; salty pretzels; the foul smell

of rain-soaked daub which coated the walls of half-timber buildings; fresh

pastries; the rotten garbage that was thrown out of people’s windows onto

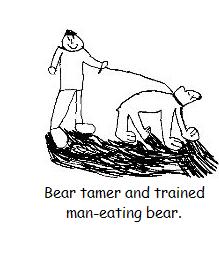

the muddy streets. But Franz hardly noticed. His rarely-washed lice-ridden

clothes were so smelly that they sufficiently masked the other smells. There were many interesting things to see – hats, gloves, musical instruments, lengths of fabric, pots and pans, girdles, swords, capes, saddles, and all sorts of other unusual things. Plus the tamed bear. A very courageous man must have trained this bear, for he was big and white. The bear tamer could make the bear stand or sit or wave its paws. The bear tamer even put his head into the bear’s mouth and lived to tell about it. Since his family was very poor, they rarely ever bought something at the fair. But this day, Franz’s father had a surprise. He had been saving up some money for the occasion. He bought each of the boys a “pig’s ear”, which was a pastry made by wrapping dough around a metal funnel, tying it with string, then frying it. They were very happy and all gave their father a big hug and an enthusiastic, “Thank you!” Not only were there things to see and smell, but there were sounds coming from every direction. Merchants were shouting; horses were clomping; water was gushing into containers as villagers fetched water from the town fountain; the glockenspiel was playing its animated and musical story about King Rudolf; and craftsmen were pounding away in their ateliers. Franz had always wanted to be a craftsman. He dreamed that perhaps he could make beautiful statues or gold chalices or carved wooded crucifixes. Becoming a master craftsman took many years. Starting at age twelve, a boy trained as an apprentice for seven years. An apprentice was not paid, but he did get a room and food to eat. He worked hard, slowly learning about a particular craft. At age nineteen, the apprentice became a journeyman. At this point, he was paid a little, but still needed to learn new skills and become more responsible. The journeyman finally created a “masterpiece.” His masterpiece was taken to the Guildhall, and if the masters of his trade thought it was good enough, then he could become a master too. Becoming a craftsman was just a dream. Franz could never become a craftsman because he was not free. Serfs were not allowed to be craftsmen.

The pier was always interesting. Boats were constantly traveling up and down the Rhine River, bringing goods to the town and castle from other towns and countries. They brought fabric, exotic woods, rare metals, and unusual animals. When they left, they usually took several large casks of wine with them. The town of Legoland was famous for the wine made with grapes from the baron’s vineyards. Franz’s father had worked hard to pick many of those grapes. As they looked toward the barbican, Franz noticed a metal rod sticking straight out. He asked his father, “What is that rod for?” His father replied, “It is a standard length that merchants must use for measuring. It helps keep merchants from cheating.” As they continued walking past the inn, Franz could smell the aroma of blood sausages and sauerbraten floating out the inn’s windows. The Inn of the Jumping Fish was known to have the best blood sausage anywhere on the Rhine. He had never tasted it himself, but from the aroma, it sure seemed like it must be the best. Behind the inn, Franz noticed beautiful flower gardens. People rarely grew flowers because they figured they could use that precious space to grow food and vegetables instead. All the same, the flowers were sure lovely to see. He thought heaven must be like a flower garden, with Mary and Jesus waiting for him there. He longed to be with Mary and Jesus. Down the dirt road were some children playing. He asked, “Father, can we play a while with the other kids?” “Yes, Franz,” his father replied. “But remember, play with the other children as though you were playing with Jesus.” “Yes, father,” said Franz and his brothers, as they skipped toward the others. First, they played hide-and-seek. Then, they played Blind Man’s Buff. One player was blindfolded. He tried to catch the other kids and figure out who they were. Finally, they played camp-ball. The team that had the ball, which was made from a pig’s bladder filled with dried peas, tried to get it into the other team’s goal. After playing all these games, they were exhausted. It was time to return home and get as much sleep as they could, for tomorrow was another long day of work in the vineyards.

Royal Visit “The Emperor is dead! Long live the Emperor!” The shout rang out from every corner of the village. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII of Luxembourg had died. Now, Louis IV Wittelsbach of Bavaria had been elected by the seven Prince-Electors as the new emperor. Even more, he was coming to visit Legoland and the Skittersburg. This meant that there would be a royal feast in the castle’s Great Hall.

In some

countries, like England or France, the king was the most powerful person.

But not so in

The baron wanted to make sure that the Emperor was given a royal welcome. He told all of the villagers to wear their best clothes and line the streets of the town. The serfs were told to stand behind the freemen so that the Emperor couldn’t see their worn and dirty clothes. As the Emperor made his way down the main street, people yelled out, “Long live Louis the Forth! Long live the Emperor!” Franz notice that everyone shouted, except for that same suspicious looking man with the black hood. The sharp-eyed man seemed to be looking very intently at the large wooden chest at the back of the Emperor’s carriage. The man grinned, then wormed his way through the crowd and headed towards the pier. As Franz had suspected, and would later find out, this man was up to no good.

Preparing for a royal feast required an enormous amount of work for the kitchen staff. The chief cook was making sure that food was properly roasted, broiled, or baked in the fireplaces and ovens. He carefully measured valuable spices which were locked away in the spice store. The baker was busy making bread. The apiarian fetched honey from the bee skeps. Scullions (kitchen helpers) carefully gathered sleeping doves from the dovecote to throw into the pot, caught fish from the castle fish pond, collected herbs from the herb garden and picked fresh fruit and vegetables from the castle garden. Servant boys called turnspits slowly turned whole animals on the roasting spits in front of the kitchen fire. The pantler carefully arranged food on plates, ready to be served. The rat catcher tried to keep rats out of the food. While food was being prepared, the baron and his guests were themselves getting ready. Since the trip to the castle had been dusty, the Royal guests took baths in a large wooden barrel. Water-carriers carried bucket after bucket of warm water up the steep stairs of the keep and filled the wooden barrel. After bathing, the Ladies-in-waiting helped the Empress and baroness dress. The chamberlain helped the Emperor and baron dress. As the Royal party approached the Great Hall, the usher opened the door for them and gave a deep bow. The Emperor, Empress, baron, and baroness made their way to the High Table. The High Table was reserved for important guests and was the only table with chairs. It was covered with fine linens. All the other guests, such as knights and significant people from Legoland, sat on benches at the low tables (serfs and other poor people weren’t invited). People at the High Table had plates; the others had to put their food on large slices of stale bread called trenchers. On the High Table were the only bowls of salt, which were in boat-shaped salt-cellars. Since the cook didn’t put salt on the food, guests had to put on their own salt. Important guests sat “above the salt” at the High Table; less important guests sat “below the salt” at the low tables. Suddenly, there was a blare of trumpets from the trumpeters standing in the gallery (the balcony overlooking the Great Hall). The feast was about to begin. This was the signal for servants called ewerers to bring bowls of warm rosewater-scented water for guests to wash their hands. Then, a steady stream of food began to be served. One course after another.

Whenever meat, fish or poultry was served, it first needed to be properly carved, or cut. This was the job of the carver, who was a young noble. The carver would “dismember” a heron, “splat” a pike, “untache” a curlew, “display” a crane, “fin” a chub, and “spoil” a hen. All of this food made the guests very thirsty. The butler was in charge of the drinks and made sure that everyone had enough to drink. He made sure that the cellarer hoisted wine up the dumb-waiter and stocked it into the cellar, the tapster drew wine and ale from the barrels, the dispensers in the buttery poured the drinks, and the cupbearers carried the drinks up to the guests. The Emperor and baron each had their own personal cupbearers who made sure that their cups were never empty. And dapifers made sure that the important guests had clean napkins. People used their best manners while eating in the presence of the Emperor. Guests were expected to know these manners: “Do not spit upon or over the table,” “If you wash your mouth out while at the table, do not spit the water back into the bowl, but instead spit politely on the floor,” “If you blow your nose, remember to clean your hand by wiping it on your clothes (there were no handkerchiefs),” “Don’t wipe your teeth or eyes with the tablecloth,” “If there is a man of God (such as a priest) at the table, take special care where you spit,” “Do not pick your teeth at the table with a knife, straw, or stick,” “Do not belch near anybody’s face if you have bad breath.” While everyone was eating, there was plenty of entertainment. The jester performed his silly antics and made everyone laugh. Jugglers and stilt-walkers performed amazing skills by throwing knives and flaming torches high into the air. Minstrels sang songs and played their instruments from the gallery. A trained monkey climbed up on the chandelier, which was burning expensive candles on this occasion. Usually, torches dipped in tar were used to light the castle. All of this talking, laughing, music, and bustling of food in and out created quite a commotion…

…which is exactly what the black-hooded man was hoping for. He peeked out the top of the barrel he had been hiding in. Then, he silently made his way across the pier, lowered himself into the cold water, and swam across the moat towards the castle. Once on the berm (narrow strip of grass) of the other side, he tossed his grappling hook high up into the air. It caught on the balcony with a clank. But no one heard. He slowly pulled himself up the rope, being careful that no sentries or lookouts saw him in the shadows. After climbing onto the balcony, he made his way through the open doors. What a strange room, he thought. Lots of bottles with strange looking liquids in them. Large pieces of lead and other metals. But no gold. “I see you,” someone said. He ducked under a table, bumping his head while doing so. Just then, an old man with a white beard and a pointed blue hat came into the room. He went over to another table, and began mixing some things. While he was doing so, another man mysteriously appeared over by the bookshelf. He looked identical to the first man. They began to talk to each other. “Did you find the eagle’s feathers?” said the first. “No, but I did find some edelweiss flowers,” replied the second. “Edelweiss flowers won’t help turn lead into gold,” said the first. “I know,” responded the second, “but they sure are pretty. By the way, wasn’t it funny yesterday when the apothecarist in town thought he had seen you taking some herbs from his garden? But when he came to the castle to report the matter, the baron assured him that he had been having dinner with you at the same time.” “Yes,” said the first, “but we need to be careful. If people find out that there are two of us, we’ll be in a lot of trouble!” Just as hastily as the two men entered the room, they both left. Since it seemed safe to come out now, he began to crawl out from under the table. “I see you.” He stopped where he was and scanned the dark room, looking for the source of the voice. “Polly want a cracker. Polly want a cracker. I see you.” There it was, over by the bookshelf. A silly parrot. He got out from his hiding place, and went over to the bookshelf. Although he couldn’t read, the books on the shelf sure seemed interesting. He pulled out one of the books to look at its cover, when unexpectedly, the bookshelf began to move. Behind it was a secret passage. He climbed through the secret opening, closed the bookshelf, and started to make his way down the passage. A bat flew past his face, startling him so that he nearly fell down the ladder. There were spiders everywhere. At the end of the tunnel, he found another secret door, made to look like a wall. He opened it, only to find that he was in the kitchen cellar. He heard someone coming down the stairs from the kitchen. He quickly hid behind a large barrel of smelly fish. It was just a scullion who had come down to fetch some salt pork. He softly moved towards the kitchen stairs, when suddenly, the floor where he had been standing opened up. A large barrel fell through with a crash at the bottom. “That was close,” he thought. By the stairs, he saw a servant’s apron and put it on to disguise himself. He made his way up the stairs towards the kitchen. “Hey you!” the pantler shouted. “Take this over to the Great Hall. It’s getting cold.” He was handed a large platter of sausages and meatballs. Another server pushed him on his way. Once in the Great Hall, he was told to put the platter on the High Table. As he slyly looked around, he noticed that the Emperor was not wearing his crown. “Good,” he said to himself. “This is very good.” “Hey you!” the butler called. “Go down to the wine cellar and see if the cellarer needs any help. We’re starting to get low on wine.” He made his way down to the wine cellar, but before the cellarer noticed him, he hid behind one of the large wine barrels. As he was hiding, he saw that there was a dumb-waiter bringing up full barrels of wine, and lowering empty barrels of wine. He had a plan. He crawled into one of the empty barrels. A few minutes later, he was being lowered down to the undercroft. Halfway down, he jumped onto a ledge. The storeman almost saw him. As he made his way around the ledge, he noticed a small room. And it wasn’t just any small room. Inside, he saw what looked like some jewels. He gingerly made his way towards the jewels, when all of a sudden a ghost seemed to fall on him from the ceiling. “Eeek!” he cried. Then, without warning, the floor opened up and he fell through. Splat! He found himself in a pile of… “Yuk!” he cried again, as he realized he was in the smelly cesspit. As he looked around, the saw a large spider web. Behind the spider web was a skeleton. A dead skeleton. “At least I’m still alive,” he consoled himself. He saw only one way out, and he didn’t like it. Nevertheless, he would have to take his chances. He started to shimmy himself up the latrine shaft. Then the worst happened. Plop! Drizzle… He waited awhile, then continued his way up. Finally, he emerged at the top, crawling through the garderobe. He found himself in the garrison quarters. This was a dangerous place to be. Luckily, the soldiers were warming themselves near a basket of hot coals called a brazier. They didn’t see him – or luckily smell him – as they were busy playing a game of dice. He spotted a ladder leading down a floor. He quietly moved towards the ladder, then climbed down. He didn’t like where he found himself. He was in the dungeon, the last place he wanted to be. Upstairs, he heard a commotion. “Thief! There’s a thief in the castle!” “Where is he?” asked one of the soldiers. Another replied, “We don’t know, but the storeman said he saw someone suspicious up on the ledge in the undercroft.”

He was in trouble now. He ran to the other

side of the dungeon. As he leaned against the wall, it abruptly opened. He

passed to the other room, then softly closed

He found himself in a dark room. He saw a little bit a daylight peeking through what seemed like another secret door on the other side of the room. The door was shaped like a large rock. That door must be the sally port, he thought, where soldiers could secretly and stealthily leave the castle. As his eyes adjusted to the dark, his mouth began to drool. What he saw were piles of jewels and gold. He had found the treasure. This is where they must have stored the Emperor’s crown. He looked and looked, but could not find it. Perhaps it was in the dark corner at the back of the room? He carefully crawled over the piles of treasure. From the dark corner, he heard a noise. It sounded like breathing, as though something were asleep. He attempted to move backwards, when he tripped over a treasure box and landed on the floor with a big thud! A pair of eyes opened, looking straight at him. He heard what sounded like a muffled miss. The eyes began to move towards him. “A dragon!” he thought. Remembering the other secret door, he began to run. He pushed open the door, and jumped. Splash! He found himself back in the moat, right where he had started. He swam as fast as he could, made his way to the pier, climbed out, and ran right out of town, never to return. As he hurriedly left, a pair of eyes watched him from the secret door. There really had not been any reason to be too scared, because it was just “Phantom”, the mischievous castle cat.

Soon after the Emperor had left, the baron decided to hold a tournament. He needed to recover some of the money he had spent on the great feast, and had an idea of how he might do it. Barons and knights came from up and down the river valley to prove how brave and skillful they were. Baron von Skitter was especially interested in challenging the rich and powerful Rhinegrave Hidelbrand. A Rhinegrave was a count who had large holdings of land along the Rhine River. Counts were typically much richer than barons because they usually had much more land. After all of the contestants arrived at the lists, which was a large grassy area where the tournament took place, the spectators in the pavilion began to yell, “Hola!” This meant that the tournament was to begin. Next, the herald announced the names of all the contestants, listing off all of the great deeds that each had accomplished.

The herald announced loudly, “And now, what you have all been waiting for! The Baron von Skitter is to challenge the Rhinegrave Hidelbrand!” As the spectators chattered among themselves about this exciting challenge, the baron’s squire helped put on his armour. First, he put on some padded underclothes. Then he strapped on his leg armour, fastened on his breastplate, and finally put on his helmet. He helped him onto his horse, then handed him his shield, which had the baron’s coat-of-arms painted on it. Next, he handed him the long jousting lance. The baron needed to win this contest so that he could make back the money he desperately needed. And just to make sure, he sent one of his spies to perform a nasty deed. While no one was looking, the spy sneaked over to the Rhinegrave’s horse and loosened his saddle. The herald yelled, “Contestants to your places!” Once they were in place, he shouted, “Charge!” As they charged towards each other, and just as their lances were about to hit each other, the Rhinegrave’s saddle came loose and he fell to the ground. The baron dismounted from his horse and ran over to Rhinegrave Hidelbrand, who was still laying on the ground. He demanded that the Rhinegrave pay 10,000 pieces of gold because he had lost the contest. Hidelbrand said, “That is a ridiculous sum of gold to pay. And besides, I do not carry that amount of gold with me.” The baron called out, “Guards! Guards! Come arrest this man and put him into the tower prison, high in the keep!” The baron looked down at the Rhinegrave and said, “You will remain in the keep as a ransom prisoner until your people pay the gold.”

When the Rhinegrave’s constable heard what had happened, he was outraged. He found out that the contest had been unfair. Also, 10,000 gold pieces was the ransom for a prince, not a count. It was too much to pay. The constable made up his mind quickly as to what should be done. He called the Captain of the Rhinegrave’s Castle Guard and instructed him to put together a large force of knights, archers, crossbowmen, pikemen, and foot soldiers. He told the carpenters to prepare the siege engines.

As the Rhinegrave’s troops massed outside the town walls, the baron’s troops stood ready. Their long bows and crossbows were aimed through the bow loops of the town’s covered wall-walk and the crenels of the castle walls. But the Rhinegrave’s troops did not attack. Instead, they just waited, making sure that supplies or people could not go into, or out of, the town or castle. “Fine,” thought the baron, “we can outlast any siege.” But there was something the baron didn’t know. One of the Rhinegrave’s spies had snuck into the castle the night before and poisoned the well. When the baron found out, he was furious. At least, there was the cistern. But that water wouldn’t last for long. In fact, it only lasted for about a week. People could go for weeks or months without food, but only days without water. After two weeks, the baron gave up and set the Rhinegrave free.

The baron was not a religious or holy man, and rarely ever stepped foot into the castle chapel. But the villagers in the town, for the most part, were religious people and loved God. Since their village had been spared destruction (thanks to the prayers of the villagers, monks, and the hermit high in the castle), they wanted some way to thank God. The bishop called for a special Feast Day. Franz especially liked Feast Days. It was then that his father and brothers would walk down the slopes and attend Mass at the beautiful Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament. On this special day, before Mass, the Bishop processed up and down the town’s streets, carrying the Relic of Christ’s Thorn, which was kept in the castle’s Chapel of Christ the King. At the end of the procession, as they prepared to enter the Cathedral, Franz craned his neck to look up at the statues of the saints. He said a little prayer to each of the saints represented –

“Saint Joan of Arc, pray for us.” “Saint Michael the Archangel, pray for us.” “Saint Christina, pray for us.” “Saint Stephen, pray for us.” “Saint Joseph, pray for us.” “Saint Mary, pray for us.” “Saint John, pray for us.”

The Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament was still many years from completion. They had already been working on it for over two hundred years. Sculptors had just recently finished the statue of St. Joan and St. Michael. In front of the Cathedral was the Mason’s temporary lodge, where the Master Mason directed all of the workers and craftsmen as they built this monument to God. By the lodge, Franz could see a section of a stained glass window. Stoneworkers carefully pieced together the narrow tracery, or pieces of stone that would hold in the glass. Glassblowers would then lay in different colors of glass and melt lead around their edges to hold them together within the tracery. Windows and statues were very important to Franz, because it was about the only way he learned about God. Since no one in his family could read, Franz’s father would take him to the Cathedral and tell him the various Bible stories that were depicted by the windows and statues, just like his own father had done when he was a boy.

Once in the Cathedral, Franz noticed a new window that had must have been put in since the last time he was here. It was a small round window of a dog biting its tail. His father told him that it represented the Devil. No matter what bad thing the Devil tried to do, God always made something better come from it. During Mass, people stood or knelt on the stone floor. There weren’t any seats. At communion time, everyone went up to the front of the Cathedral and waited their turn to kneel at the altar rail. Perhaps fifty people could kneel at the same time. Father would go back and forth, giving communion to each person. As Franz knelt there after receiving the Eucharist, he thanked Jesus for coming down to live inside of him. After Mass, Franz’s father, Friedrich, said that they could watch the Miracle Play which was just starting in front of the Cathedral. Troubadours, minstrels and mummers (traveling actors) had come from another town to put on the play. They had brought their own stage with them, which was on wheels. Today, the play was about St. George and the dragon. When they were in town, they also liked to visit the Monastery Church of the Nativity. It was not as large as the Cathedral, but it was very beautiful. It was in this church that the monks would chant their office (say their prayers together). There were eight times during the day that they did this. The first office was Matins, which was at two o-clock in the morning. In the middle of the day, at noon, was the Angelus. In the evening was Compline and finally Vespers before they went to bed. Sometimes, the monks were so tired that they could hardly even get out of bed to say their office. Someone even wrote a song about one of the monks, Brother John.

Are you sleeping, are you sleeping, Brother John, Brother John? Morning bells are ringing, morning bells are ringing, Ding-ding-dong, ding-ding-dong.

Between prayers, the monks would read or work in the scriptorium copying books. Some of the monks helped take care of the poor by giving them food in the almonry. Others helped the sick in the infirmary. The monks in this monastery followed the Rule of St. Augustine. Following a rule, or certain way of life, helped to develop discipline and obedience. Just like children need to be obedient to their parents so that they can learn to be obedient to God, monks also need to learn to be obedient. Outside the monastery there was a group of children, standing about Brother Andrew. The brother was a kind monk who helped the children learn their catechism. After the lesson, the children would recite their prayers. If they did well, Brother Andrew would give them a pretzel. For hundreds of years, monks would give out pretzels as rewards to children who had learned their prayers. The first pretzels started in a seventh century monastery. A young monk preparing unleavened bread for Lent realized he could take the leftover dough and twist it into a shape similar to the way people prayed at that time. Christians, especially children, prayed with their arms folded across their chests, each hand on the opposite shoulder. Franz was especially pleased to receive a pretzel. He had been practicing his prayers very hard. As he and his father and brothers were about to enter into the quadrangle (or courtyard) in front of the monastery church, Franz noticed a poor man without any hands. He was begging for alms. Franz didn’t have anything except for the pretzel, which he had hoped to eat as his lunch. But Franz figured that this man needed it more than he did. Once in the church, Franz admired the large window of the Nativity. He was so pleased that Jesus had come down to earth to save a poor boy like himself. From far and wide, pilgrims would come from other towns and villages to visit this church, and its precious relic. Beneath the church, in the crypt, there was a gold reliquary that contained a drop of the precious myrrh which had been given to Jesus by the wise men. While visiting, the pilgrims would stay in the monastery’s hostel, which was free. On the main floor of the church was a diagram of a large labyrinth, or maze, made from hard stone tiles. Pilgrims would walk through the maze on their knees. While they did this, they would pray and imagine that they were making a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and the Holy Land.

That evening, as Franz and his family were returning home, there was a great noise coming from down the dirt road. Around the bend, two horses suddenly appeared, galloping at top speed. Friedrich and his sons tried to get out of the way. Franz pushed his brother Mark to safety. But he himself tripped on a stone and couldn’t get out of the way. Neither could his father. The horseman – the baron and his son, Rolf – paused for a moment to see the damage they had caused. The horses had trampled over Friedrich’s legs. Johann and Mark were okay, but Friedrich’s beloved son Franz lay there – lifeless. Franz was dead. The baron laughed and called out, “Stupid serfs! Watch where you’re going!” As the horsemen continued on their way, Rolf turned back and gave Friedrich a nasty smirk.

That winter was especially hard and bleak. Not only had there been a bad harvest, but the great feast used up much of the town’s supplies. The siege by the Rhinegrave’s troops did not help matters. Everyone’s stomachs were half-empty, and sometimes, completely empty. Franz had been given a simple funeral and was laid to rest in the common graveyard. They grieved the loss of gentle Franz who used to cheer them with his stories during the dreary winter evenings. Friedrich’s legs were of little use since the accident. He could only hobble around on a pair of make-shift crutches. One cold winter day, as Friedrich tried to collect a bit of firewood, he heard a faint voice. He carefully and feebly moved towards the voice along the slippery slopes of the vineyard. There, at the bottom of a pit, was the source of the cry. It was Rolf. He had been sledding down the slope and had fallen into the pit. His sled lay next to him at the bottom. If Rolf did not get out soon, he would freeze to death as the weather was quickly turning colder. Friedrich, who was always prepared, took out a length of rope from his knapsack. He tossed the rope down to Rolf. But because his legs were weak and the ground was so slippery, he was unable to pull up Rolf without falling into the pit himself. At this point, Friedrich thought it would be best to get help. But when he tried to get up, his crutches suddenly began sliding down the slope. They were gone. He had to think of another plan. A little way above the pit, Friedrich noticed a tree. He took the rope and tossed it around the tree. He held onto one end of the rope, and threw the other end back down into the pit. Since Rolf’s arm was broken, Rolf wouldn’t be able to climb up by himself. Friedrich called down, “Rolf, loop the rope around yourself, and then get ready. You’re about to have the ride of a lifetime.” “Ready, set, now!” Friedrich yelled. He moved himself towards the edge of the pit, then allowed himself to fall in. As he fell, Rolf was quickly pulled up. Now, Rolf was at the top, and Friedrich was at the bottom. Rolf called down, “Why did you help me?” Friedrich replied, “Would Jesus do any less?” Rolf took one last look at Friedrich at the bottom of the pit, then proceeded to walk slowly back to the Skittersburg. Once at the castle, Rolf decided he shouldn’t mention what happened, because his father was sure to be angry and would give him a harsh whipping. That night, as Rolf laid on his straw-filled bed, he could hear faint sounds of the Ave Maria echoing through his open window. He tried covering his ears, but it did no good. He finally fell asleep, only to be awakened by a dream of the boy Franz crying over his poor father. Rolf could take no more of this. He rushed to the solar, the family’s large living room, to find the baron sitting before the immense fireplace. He told his father everything that happened – how he had carelessly fallen into the pit; how Franz’s father risked his life to pull him out. Much to Rolf’s surprise, the baron listened intently, but did not become angry. Instead, he just sat there for what seemed like hours. Thoughts kept running over and over through baron’s mind. He had recklessly crippled Friedrich and killed his son, Franz. Worse yet, he had laughed about it. It would only seem fair that Friedrich should have the last laugh by allowing Rolf to die at the bottom of that pit. Why didn’t he? Why didn’t he!? Suddenly, the baron covered his face with his hands and began sobbing uncontrollably. By morning, there were no more tears left to come out. “Why am I sitting here?” said the baron to himself. “What a fool am I!” The baron rushed down from the solar and quickly assembled a rescue party of his best knights. They hurried up the icy slope. But alas, it was too late. At the bottom of the pit, all they found was a frozen man holding a horn to his frozen lips.

Baron von Skitter could not believe what had happened. He pondered it long and hard. After several days, he was finally drawn towards confession and reform. He set the rest of Friedrich’s sons, Johann and Mark, free. Then, he decided to leave the castle and join the Augustinian monastery. He became a good monk. He grew a long gray beard and was known simply as “Brother Jakob.” To make up for his terrible past sins, he took it upon himself to care for the sick and poor in the almonry and infirmary. He lived a humble and saintly life, and after he died, was buried in the monastery cemetery. When he was later dug up (on account of all the miracles attributed to his intercession), it was found that his body was incorrupt. He was then laid to rest in the Monastery Church of the Nativity.

As for Friedrich’s sons – After gaining his freedom, Johann became an apprentice to a tinker. Tinkers made pots and pans, and could fix just about anything. Johann worked hard and made his way through journeyman, then finally became a master. He started his own atelier across from the monastery. He married and had ten children. Young Mark joined the monastery. After a time, he learned to read and write. Because his handwriting was so beautiful, he was put to work in the scriptorium copying Bibles by hand. Copying a Bible was monotonous work and could take up to three years. Mark wrote on a special type of paper called vellum, which was made from sheepskin. It took one thousand sheep to make a single Bible – no wonder they were chained up in churches and schools, so that others could read them. Franz had received his reward and was now in heaven’s flower garden with Jesus and Mary and the saints. He was reburied in the crypt of the Cathedral and honored as a saint. As for Friedrich, he also was honored as a saint and laid to rest in the crypt below the castle’s chapel.

What about Rolf? In time, he became a knight – an honorable knight. He took control of the castle and ruled the town and farms with compassion, justice and generosity. It was then that he renamed the castle to the Hoernersburg (“Horn-blowers castle”) after the hero who had saved his life – Friedrich, the “horn-blower”.

…and if you listen carefully on a cold winter’s night, some say that you can still hear the faint sounds of the Ave Maria echoing up and down the Rhine River valley.

|

More

►Tour Stop 1: Lego Castle & Great Hall

►Tour Stop 3: Castle Outer Ward

►Tour Stop 4: Medieval Lego Town

►Tour Stop 5: Cathedral & Monastery

▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬▬

►Let us know how you like our site

►Tale of the Hoernersburg << you are here

Villagers were required to pay many

different taxes. One tax called a multure had to be paid in order to

have one’s corn ground at the castle windmill. Villagers could not even bake

their own bread. Instead, they had to pay to have their bread baked in the

castle bakery’s great oven.

Villagers were required to pay many

different taxes. One tax called a multure had to be paid in order to

have one’s corn ground at the castle windmill. Villagers could not even bake

their own bread. Instead, they had to pay to have their bread baked in the

castle bakery’s great oven.

As they walked around the village eating

their pig’s ears, they noticed a nervous looking man with a black hood. He

was leaving the inn and seemed to be in a hurry. He rushed past a shopkeeper

sweeping the walkway and nearly knocked him over. The mysterious man

hurried down the street, passed through the barbican, and walked down to the

pier. Franz wondered if he had come on one of the boats docked at the pier.

As they walked around the village eating

their pig’s ears, they noticed a nervous looking man with a black hood. He

was leaving the inn and seemed to be in a hurry. He rushed past a shopkeeper

sweeping the walkway and nearly knocked him over. The mysterious man

hurried down the street, passed through the barbican, and walked down to the

pier. Franz wondered if he had come on one of the boats docked at the pier. Germany. Germany was ruled by an Emperor, who was like a king

of kings (which would make Jesus a king of kings of kings).

Germany. Germany was ruled by an Emperor, who was like a king

of kings (which would make Jesus a king of kings of kings).  the secret door.

the secret door. Then, the jousting began. Knight after

knight charged at each other on their horses. Separating the knights was a

long fence, called a tilt. Their lances were aimed straight ahead in an

attempt to knock the other knight off his horse. The loosing knight had to

pay by giving up his armour or horse. Some knights even paid with their

lives because this was such a dangerous sport.

Then, the jousting began. Knight after

knight charged at each other on their horses. Separating the knights was a

long fence, called a tilt. Their lances were aimed straight ahead in an

attempt to knock the other knight off his horse. The loosing knight had to

pay by giving up his armour or horse. Some knights even paid with their

lives because this was such a dangerous sport. The castle lookout at the Skittersburg

was the first to see the Rhinegrave’s troops from the watch turret, the

castle’s highest lookout tower. This was not what the baron had expected,

but he was prepared nevertheless. The food store high in the castle keep was

loaded with food. The town gate had been closed. The portcullis had been

dropped and the drawbridge raised.

The castle lookout at the Skittersburg

was the first to see the Rhinegrave’s troops from the watch turret, the

castle’s highest lookout tower. This was not what the baron had expected,

but he was prepared nevertheless. The food store high in the castle keep was

loaded with food. The town gate had been closed. The portcullis had been

dropped and the drawbridge raised.  Some of Franz’s favorite

statues were above the doorways in the tympanum’s, or recessed spaces. Above

the left doorway were the bones of a dead man. This showed that all of us

will die someday and that death seemed like it would be the end of our

existence. Above the central doorway was Jesus on the cross, with his poor

Mother at the foot. This showed that by dying on the cross, Jesus solved the

problem of death. Above the right doorway was an empty tomb. This showed

that by rising from the dead, Jesus defeated death forever.

Some of Franz’s favorite

statues were above the doorways in the tympanum’s, or recessed spaces. Above

the left doorway were the bones of a dead man. This showed that all of us

will die someday and that death seemed like it would be the end of our

existence. Above the central doorway was Jesus on the cross, with his poor

Mother at the foot. This showed that by dying on the cross, Jesus solved the

problem of death. Above the right doorway was an empty tomb. This showed

that by rising from the dead, Jesus defeated death forever.